PAH Is a Serious Complication of CTD1

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH, WHO Group I) is a progressive syndrome resulting from restricted blood flow through the pulmonary arterial circulation.2

PAH LEADS TO2:

PAH LEADS TO2:

- Reduced cardiac output

- Reduced cardiac output

- Right heart failure

- Right heart failure

- Death

- 30% mortality rate at 3 years from diagnosis observed in the REVEAL Registry

- Death

- 30% mortality rate at 3 years from diagnosis observed in the REVEAL Registry

PAH SUBGROUPS INCLUDE3:

PAH SUBGROUPS INCLUDE3:

- Idiopathic PAH

- Idiopathic PAH

- Heritable PAH

- Heritable PAH

- Drug- or toxin-induced PAH

- Drug- or toxin-induced PAH

- PAH associated with other diseases or conditions, including connective tissue disease (CTD)

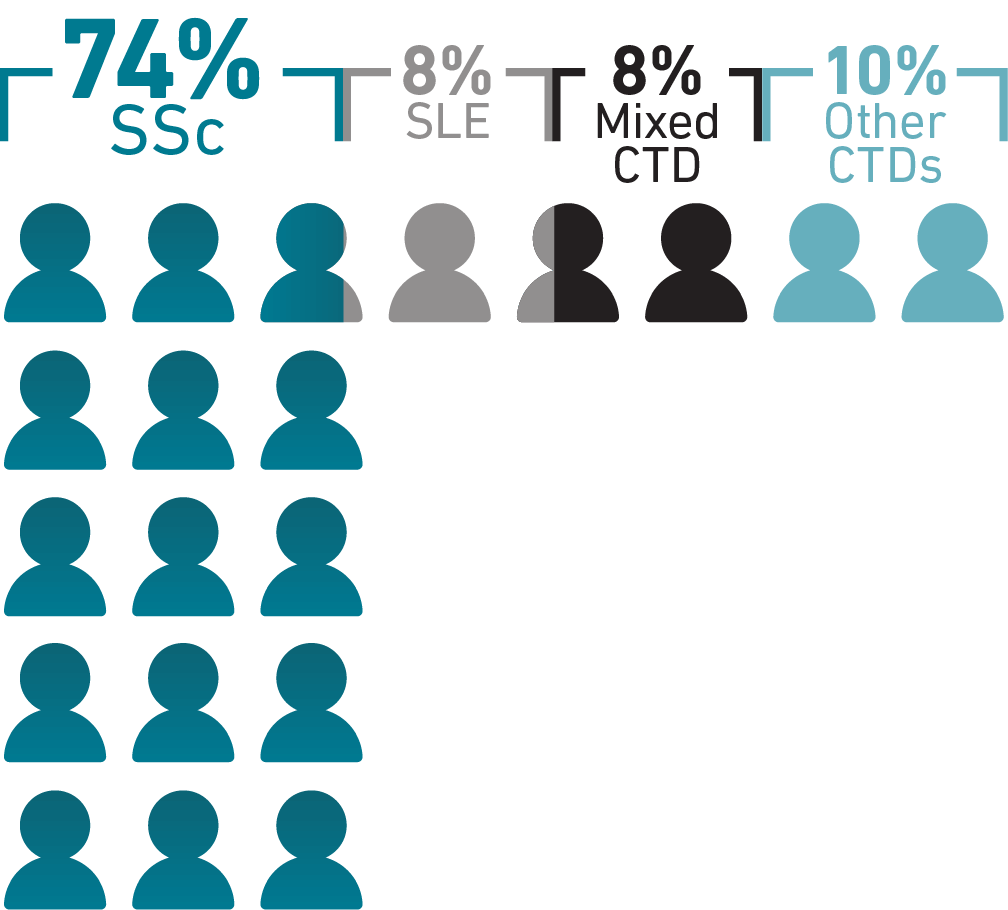

Prevalence of PAH-SSc

PAH associated with connective tissue disease (PAH-CTD) is the second most prevalent type of PAH (after idiopathic PAH) in Western countries/territories.3

PAH-CTD is more prevalent in women than men (4:1 ratio)3

PAH may be a serious complication of CTD such as3:

- Systemic sclerosis (SSc)

- Systemic sclerosis (SSc)

- Mixed CTD

- Mixed CTD

- Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)

- Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)

While SLE and rheumatoid arthritis are among the most common CTDs, PAH occurs most

frequently in SSc, with 74% of PAH-CTD cases being diagnosed in patients with SSc.1

~100,000 people living with SSc in the United States4

In DETECT, an international study of adults with SSc at increased risk of PAH (N=466), 19% were confirmed to have PAH-SSc5*

In the DETECT study,44% of patients with PAH-SSc with follow-up data (25/57) experienced disease progression within a short period of time (median observation time, 12.6 months)6*

PAH-CTD in African American Patients

PAH-CTD in African American Patients

PAH-CTD may disproportionately occur in African Americans

compared with other races.7 That disparity may persist in PAH-SSc:

African American patients were 2.5 times more likely to have PAH-CTD than non-Hispanic White and Hispanic patients in the National Biological Sample and Data Repository for PAH (PAH Biobank)7†

In a 2003 single-center US study, 48% of African American patients in a scleroderma center (n=130) had PAH, compared with 39% overall (n=709)8

Another study reported that African American patients (n=29) had greater disease severity at PAH-SSc diagnosis, including worse FC, right ventricular function, NT-proBNP, and 6-minute walk distance than European American patients (n=131)9‡

In 2 studies using national registries of death certificate data, African American women had the highest mortality rates of patients with PAH7§

Pathogenesis of PAH

SSc is a chronic, inflammatory, autoimmune disease characterized by endothelial dysfunction and microvascular disease.10-12 This baseline inflammation and endothelial dysfunction contributes to the development of associated PAH, followed by vasoconstriction and vascular remodeling and eventual right heart failure.1,10

CHANGES IN PULMONARY ARTERY

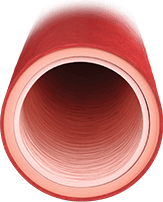

HEALTHY ARTERY

Healthy endothelium regulates13:

- Vasodilation/vasoconstriction balance

- Inhibited smooth muscle cell proliferation

- Low-resistance vasculature

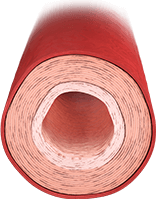

ARTERY WITH EFFECTS FROM PAH

- Earlier-stage PAH is characterized by smooth muscle hypertrophy and vasoconstriction14

- Overproduction of vasoconstrictors such as endothelin-1

- Underproduction of vasodilators such as nitric oxide and prostacyclin

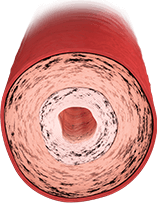

ARTERY WITH WORSENING SIGNS OF PAH

Proliferative features predominate

in later stages14:

- Increased vasoconstriction

- Obstruction from plexiform lesions and in situ thrombosis

Delayed Diagnosis of PAH-SSc

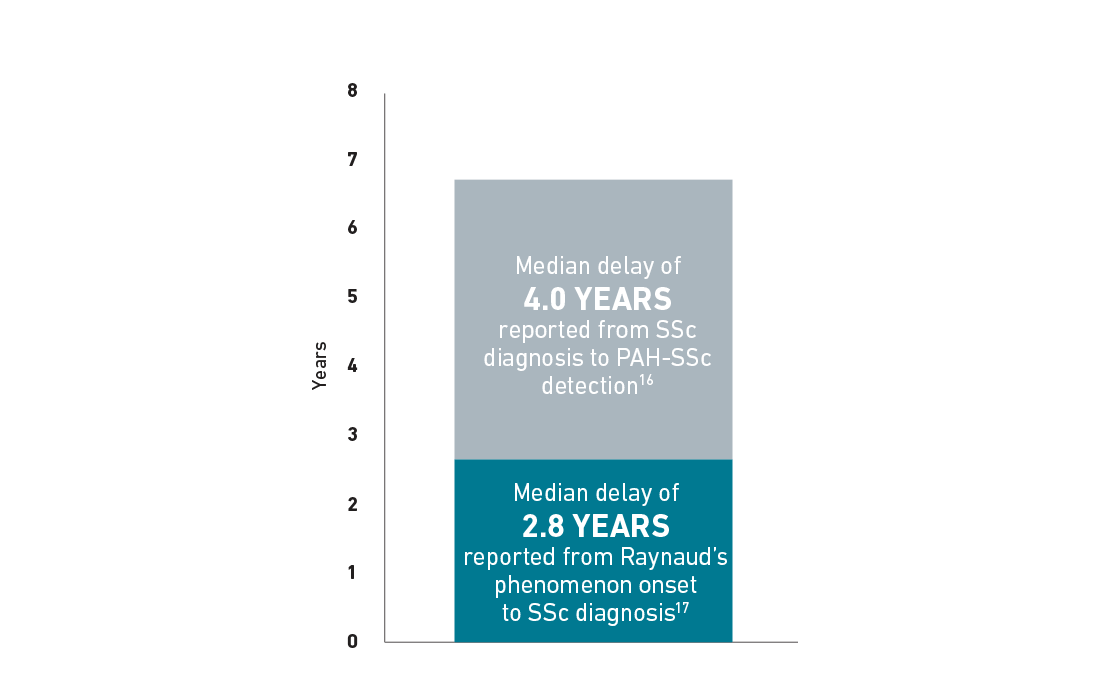

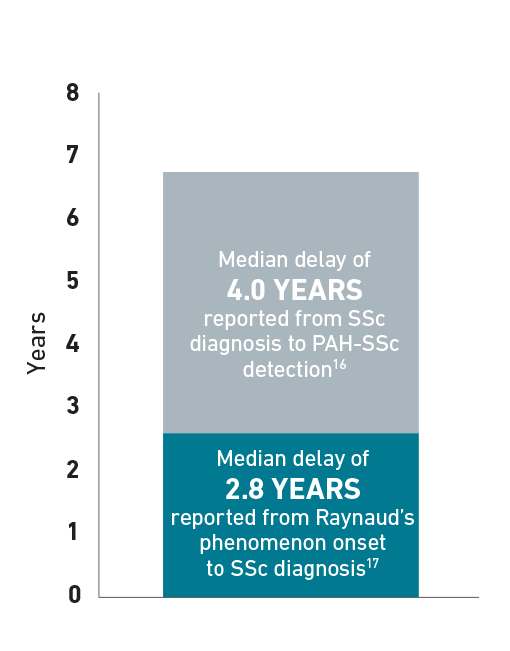

Patients with SSc can develop PAH at any time, but experience a median delay in diagnosis of 4 years.16 The following chart is an example for illustrative purposes only to portray the delay in diagnosis of PAH-SSc that a patient may experience. In some patients with SSc, median time to diagnosis of SSc after Raynaud’s phenomenon onset was 2.8 years.17 Additionally, median time to diagnosis of PAH in patients with SSc was 4 years.16

Delay in PAH-SSc diagnosis16,17

Symptoms and Risk Factors

Awareness of symptoms and predictive risk factors can help identify PAH in patients. Misdiagnosis and delayed diagnosis may be attributed to the nonspecific nature of the presenting symptoms.18,19

Symptoms of PAH-SSc10

Dyspnea

Fatigue

Orthostasis

Chest pain/angina

Lower extremity edema

Syncope

Regular screening followed by diagnostic right heart catheterization is required to consistently detect PAH-SSc.20

Risk factors for PAH-SSc21,22

Time-Related Risk Factors

- Older age at scleroderma onset

- Long-standing disease

Coexisting Conditions

- Limited cutaneous scleroderma

- Cutaneous telangiectasias

- Severe digital ischemia

- Severe Raynaud’s phenomenon

Diagnostic Results

- Nucleolar pattern of antinuclear antibodies

- Anticentromere antibodies

- Declining or isolated low Dlco

- Low FVC %/ Dlco %